How do you describe your own art practice?

I like to think of my work as homages – tributes to the peoples, places, things, and stories that have shaped who I am today. They’re also perhaps proxies, or escape routes, so I don’t always have to face the ghosts that haunt me head-on. Meandering searches and tracing nexus by association build worlds that help me interpret the haunting.

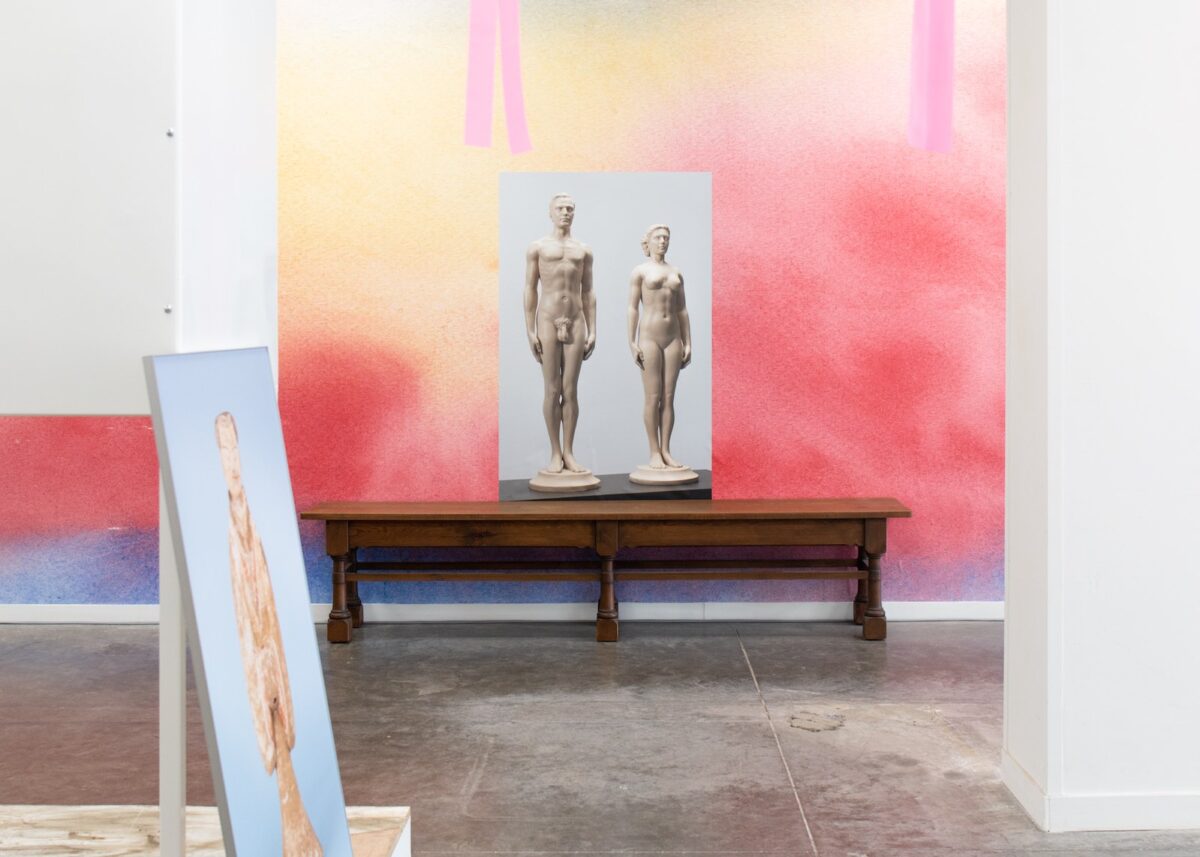

‘Ghost Eat Mud’ is a Cantonese expression vividly describing the incoherent way someone speaks. It was also the title of my 2022 project at Kunsthal Gent. In this context, the “ghost” points to a kind of storytelling that defies linear structure. That loops across multiple spaces and timelines, and features protagonists often omitted from dominant narratives – protagonists like ghosts or spirits, present yet hidden in plain sight.

Which question or theme is central in your work?

My current focus is kinship – shaped by migration, memory, and the interplay between personal and canonized histories. Living in diaspora, I’m drawn to the tensions between belonging and unmooring, heritage and hybridity. My work weaves together bio(mytho)graphy, folklore, and cultural artifacts born of geopolitical realities in the Asia-Pacific.

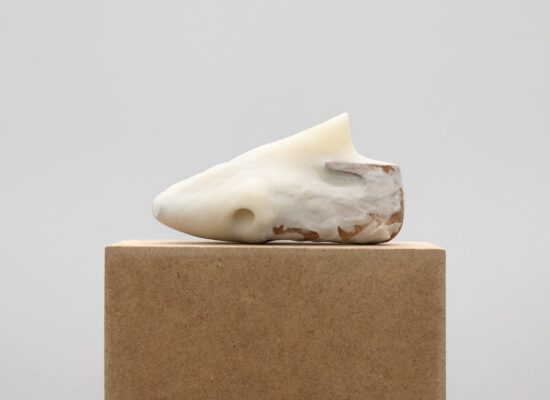

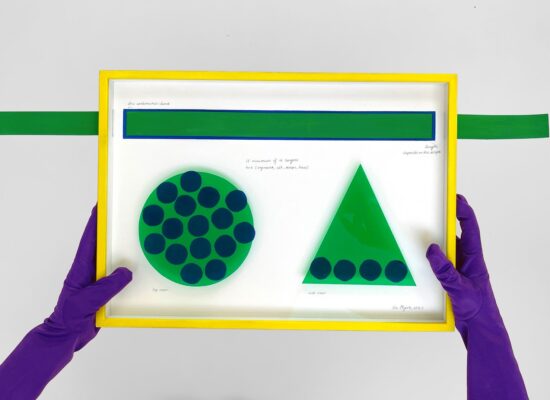

The idea of shapeshifting – the ability to code-switch, to blend in, to traverse realms – has become a guiding metaphor and a literal survival strategy, embedded in my work. Through sculpture, installation, video, drawing, and public intervention, I navigate states of migratory restlessness, using materials and traditions that range from sancai (tricolor) ceramics and institutionally loaned objects to motorized mechanisms.

What was your first experience with art?

Disney and Céline Dion, among others. Pop culture is how peoples of the periphery approximate themselves to the center. A precarious demographic – whether an underrepresented group or children and youth – may not know the latest world event, but can likely name the next anticipated release from a cultural icon.

Growing up in 1990s Taiwan – a former Japanese colony emerging from a nationalist government’s Martial Law era – my childhood worldview was unknowingly shaped by post-war American agenda and imperial legacies. The information that reached the island was carefully calibrated to instill a Westward aspiration and a false sense of liberation and self-realization.

Sugarcoated in captivating imagery and soundscapes were values that could both uplift a child and plant a deep, existential sense of deprivation. I daydreamed plot detours to insert Asiatic sidekicks in Disney classics; in sketchbooks I drew myself alongside the animated Euro-American heroes. My earliest imagination was, in a way, approximating Whiteness.

Concurrently, Céline taught me English. Her music – swooning, dramatic, and filled with big emotions but with very little at stake – was the perfect distraction any small person needed to look away from bigger, more complex realities.

What is your greatest source of inspiration?

My family. In particular, the women in my family.

My maternal grandmother was a fruit farmer who supported a large family in post-war Taiwan. My mother became a lifelong teacher who taught preschool and elementary school children, in Taiwan and in the U.S. My sister, a first-generation immigrant, birthed and raised two children while studying medicine. My aunties and cousins, who are caregivers and educators, too – the list goes on.

The idea of labor, nurture, and propagation runs deep in my family and is foundational to my work – both in content and in process, in how I treat and manipulate my materials.

What do you need in order to create your work?

I need to work with my hands. The world overwhelms me immensely these days. Laborious processes calm me and help redistribute the weight of my thoughts.

I also need a lot of help. I’ve learned that I can’t realize what I envision all on my own. I deeply admire my team and their expertise, talents, wisdom, and patience. I pray they never grow tired of me.

Right now, I’m in the process of relocating my practice. The thought of finding a new team is intimidating, but I hope to eventually connect my support systems across continents, and continue learning from them.

What work or artist has most recently surprised you?

I’ve been learning Dutch as part of an integration course in Belgium. A recent class assignment was to give a 5-minute presentation on a “famous” Belgian person using our beginner-level vocabularies and sentence structures (Dutch Level 3). I chose to talk about Francis Alÿs.

Spotlighting his work to a class of multinational, non-art-background Dutch learners, I was once again moved by how simple and powerful his practice is. There’s no superfluous and awe-inspiring technology, no embellished, maximalist space-taking, just humanist curiosity, patience, and poetry.