Based in Rotterdam, The Netherlands

Website https://rubyreding.com

Research project all this distance

Location Piet Zwart Institute, Rotterdam

Can you describe your research project?

My research project starts from the observation that our understanding of the distribution of common resources is detached from our everyday lived rhythms, creating a level of sleepiness, repression, latency, in noticing where our tap water comes from, or where the electricity from the light switch comes from, or how we can call someone who lives 2000 miles away. Ara Wilson (2016) has written how thinking intimacy and infrastructures together is a process of ‘calling attention to a telephone wire—or these days, to a cell phone tower: that infrastructures are involved in social relations and, in many cases, shape the conditions for relational life.’ I want to ask how artist film might conjure atmospheres of infrastructural dread, distance, and collapse.

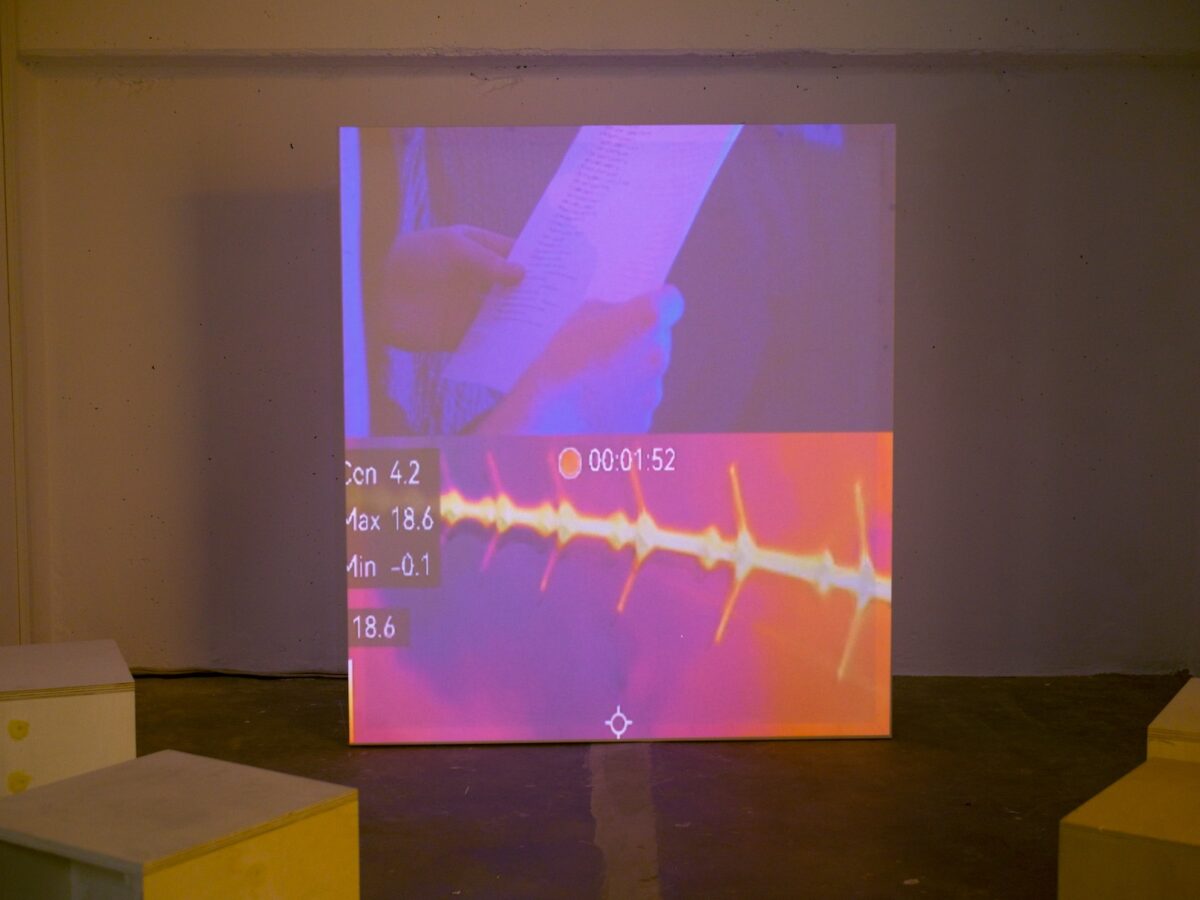

My current project thinks infrastructure and intimacy together through a filmic language of closeness and distance, exploring different locations in the Netherlands and the UK; from colonial-era wave engineering structures to meteorological measuring sites. I have followed atmospheric scientists as they test levels of toxicity and deep sea cable technicians installing cables connecting energy grids in sand dunes. Thinking through cinematography and scrap metal, I want to conjure an affective language around these sites, and the ensuing intimacy of everyday life that surrounds this research; feeling out electrical pulses, psychic and romantic webs, entanglements with measuring apparatus, clocks, conversations or birds found there.

Why have you chosen this topic?

I grew up moving around a lot, always having long distance relationships; so intimacy often felt like this digital (close) and physically (far away) phenomenon. When I moved from London to Rotterdam to study, I was struck by how much more polluted the air felt, and the ways we feel this in our lungs (close), yet the source of particulate matter is so abstract (far away). When I checked the air pollution index, I discovered the number was double in Rotterdam what it was in London, because of the city’s position near the port. We in the West are spending so much money on predictive technologies and scientific research to meet EU climate standards, and yet there is a stagnancy in the face of multiple emergencies. Our awareness about issues often doesn’t translate into action; why is that? I really wanted to convey this dissonance I’ve encountered, and use artist film and field work as a way of sitting with the complexities of pollution, of atmospheres, of what we are doing to the world and each other.

What research methods do you use?

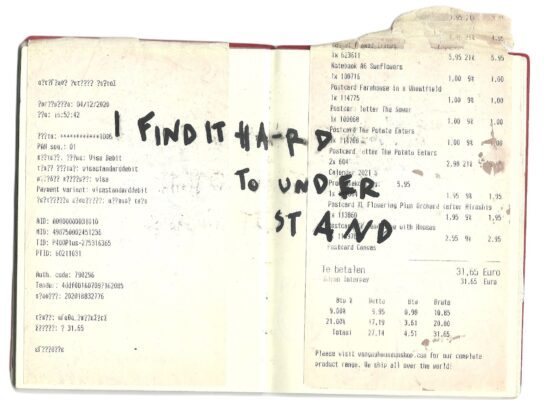

My research process involves talking to scientists, visits to local and national archives, filming, field recordings, writing poetry, taking iPhone and thermal photographs, collaborating with friends and performers, and collecting scrap material. I always start by spending time in the locations I’m researching, taking several trips with my bike, and I usually only bring a small phone camera to start with. Taking provisional image records of my surroundings and these locations helps me start to build a diagram, which I digest through collage, aiding me in finding the connections between different sites and compositions.

I’m inspired by Bridget Crone’s writing on artistic fieldwork in Fieldwork for Future Ecologies and by decolonial anthropologists such as Anna Tsing and Zoe Todd. I’m always thinking about how to interact with the environment without recreating more conditions of Western extraction, and I’m sure failing at that. Research in the field, as an artist, is like always being a novice and never an expert; maybe that’s what artistic research can do; show us how things happen and connect without explaining these ideas from a position of dominant knowledge.

In what way did your research affect your artistic practice?

Field research often inspires me to start making a film, because it situates me in the world, gets me talking to people and out of the studio. But research can also be really blocking to the creative process; they are like these two poles that you have to make dance with each other, and sometimes they don’t want to get on. Sometimes I just want to cut metal up in the workshop or write poetry in bed. I don’t think research should have to justify practice, but it can be a portal to finding new locations to film, to making more empathic and ethical material decisions, or to orienting me in the country I’m living, in the political conditions that shape our present. Research also makes me feel connected to other fields outside of the art world, towards politics, anthropology, science, queer studies, environmental humanities; and it’s nice to feel that the films and installation I make can be porous to other disciplines; they exist relationally.

What are you hoping your research will result in, both personally and publicly?

all this distance urges people to feel something about the conditions of overly saturated communication, toxicity and slow violence we’re living in. I hope the resulting film will travel to different screening locations in and outside the art world, and open up big and small dialogues with local communities about the potential of moving images, perhaps through workshops and talks. Personally, this project is a way to combine all the different fields I’m interested in, and to be both inside, outside, collaborative, alone, without too many rules, a reason to get out of bed…