Based in Brussels, Belgium / The Hague, The Netherlands

Website https://rachelbacon.com

Research project What's the Matter? An Exploration of the Shared Space between Mark and Surface in Drawing and Mining

Can you describe your research project?

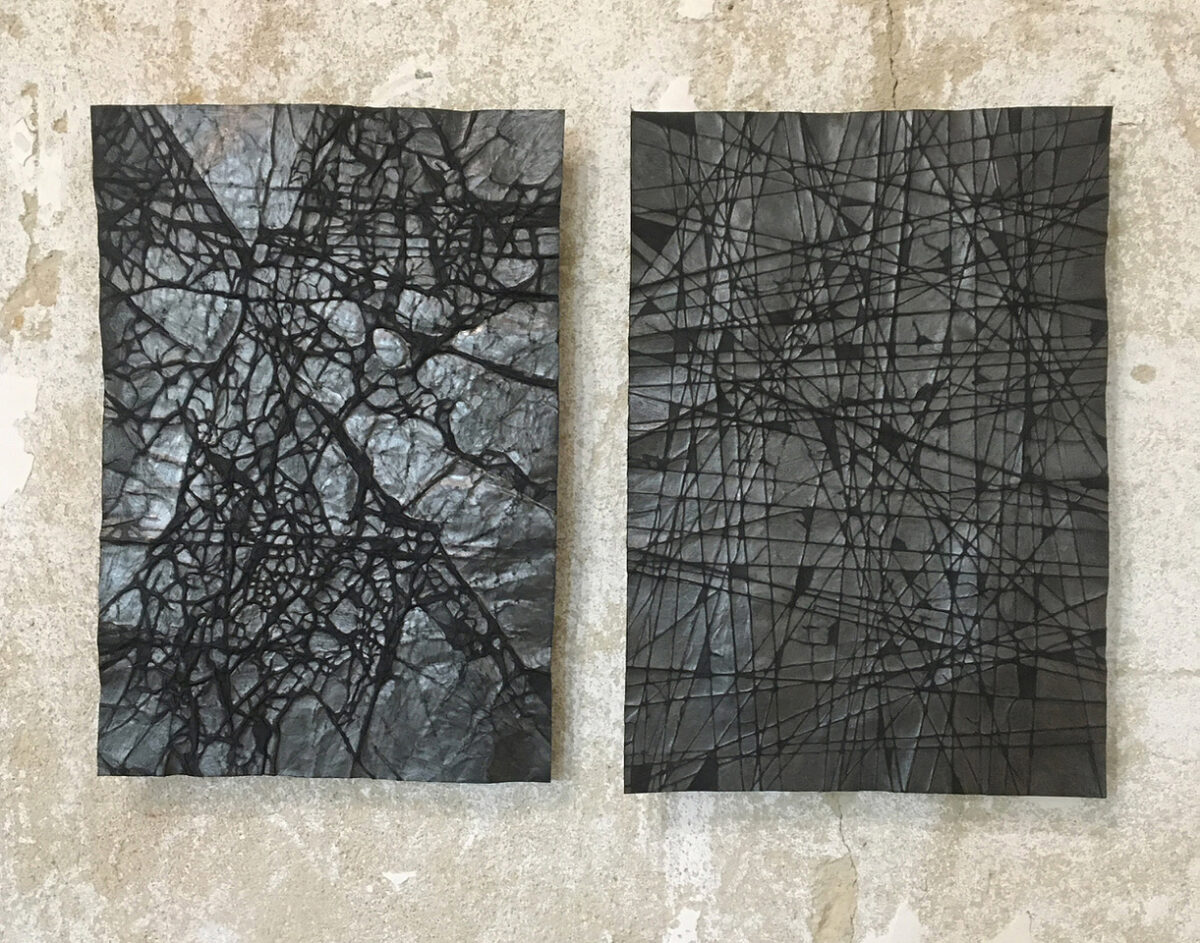

In this ongoing research project I explore the multilayered relationship between drawing, mining and landscape. I consider open-pit mining sites as forms of expanded drawing, in which extraction leaves negative marks on the surface of the landscape. In my practice, instead of seeing the landscape or the blank sheet of paper as something empty that can be acted on by a dominant form of mark making, I explore a collaboration with the surface. All my drawings are made on crumpled and damaged paper. I draw around the crumple, so that lines in the paper gradually emerge as a result of meticulous attention, and a similarity between the damaged surface and bodily forms such as skin and veins starts to emerge. Drawing on damaged paper for me is an extractive reversal, an attempt to re-imagine an interaction with our surroundings as a form of ecological co-creation, in which both surface and mark are interdependent.

The site visits I make to mining areas have resulted in a wealth of material that I am gradually incorporating into installations and presentations, together with the drawings made in the studio. Dissonant temporal layers are combined, from ancient geologic time, ever-accelerating economic time, and the unstable feedback time of climate change. Into these temporal zones, I introduce the decelerated artistic time of painstaking and meticulous drawing. Evolving a non-hierarchical and multilayered approach in which materials, artworks and archival research is combined is the next phase of the project.

Why have you chosen this topic?

This work for me began with an Arts and the Environment fellowship at a residency in Canada. In the mountains, I saw the connection for the first time between my drawing and geologic time, between the fragility of the damaged paper and the visible changes in the landscape due to the ecological crisis, such as melting glaciers and imploding rock faces. Further exploration of this topic led me to make the connection between drawing and mining, and extraction as a negative form of mark making. Opening up the idea of drawing as an expanded practice that moves beyond the boundaries of the edge of the paper has allowed me to start to address some of these issues within my work. The question for me is mainly how do we as artists work towards shifting perspectives towards less destructive outcomes? Is this even possible?

What research methods do you use?

My main research method involves site visits to mining areas to absorb the destruction of these landscapes. There is something inexpressible about the damage done, that involves witnessing and presence. I try to spend time there, to absorb and observe the aftermath and complexity of these places. This involves making photographs, sketches and meeting and talking with those living and working in these areas. As my focus is often on the aftermath of destructive human activity, I also collect traces in the form of graphite rubbings and found materials. Investigating photographic archives is an important tool in trying to envision the past and see the changes over time.

Following on from the field trips, I work in my studio on drawings that allow me the time and space to sift, remember, concentrate and digest the material. These drawings are semi-abstract, semi-sculptural, damaged and polished to an equal extent, inhabiting an in-between space. They are my embodied response and reaction to the visits to the mining sites. I am constantly exploring new ways of making drawings, from reclaiming my own leftovers, adding layers and lamination, finding new patterns and types of marks, and most recently, combining the drawings with photography.

In what way did your research affect your artistic practice?

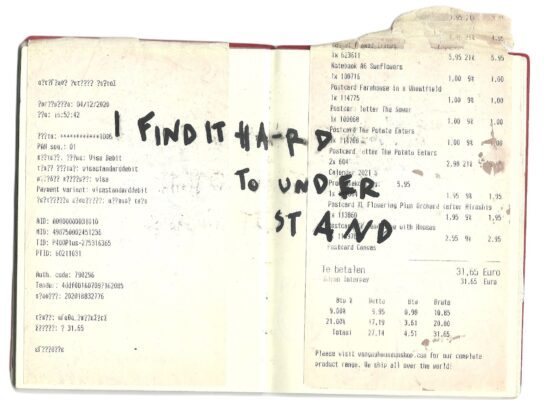

The research has deepened and enriched the possible readings of my work, and connected it to a broader conversation. While it is sometimes hard to do, I also feel it’s very important and has given me a lot of new energy and focus. From drawings that could be read as quite formal, the associative possibilities have opened up considerably through the research. It’s important for me to approach the topic of excavation as an artist, as within this practice there is the possibility of contradiction and complexity, that is often overlooked in more mainstream discourses. The possibility as well to engage in open-ended, long-term research is very valuable and something I appreciate being able to do within my work. The research has also made me much more attuned to the materiality of my work, and how that reaches far beyond the boundaries of what meets the eye.

left: Adrift, 2022, graphite on paper on foil, 35 x 265 x 165 cm

right: XD GRIP 27.00 R49, 2024, 240 x 280 cm, print on PET recycled nylon cloth

What are you hoping your research will result in, both personally and publicly?

It’s a question of a slow drip – drip – drip of attention and returning each time to a topic that will hopefully shift attitudes and perspectives. The task is probably impossible, and others have been very hard at work on it for years, and the situation is still dire. So all one can maybe hope for is to say, I didn’t give up, and I kept at it. Personally, I just wish to keep on working and to share in this conversation that I think is incredibly important with other people, through exhibitions, talks and dialogue, and through writing and making publications. Eventually, I would like to make a kind of log or playbook for working in damaged landscapes that might be a guide for other artists and students. My role in teaching is another means of sharing these issues and ideas with a broader audience of makers and thinkers.