Based in of Polish origin, currently living and working internationally (at the moment mainly between Switzerland, Scotland and the Netherlands)

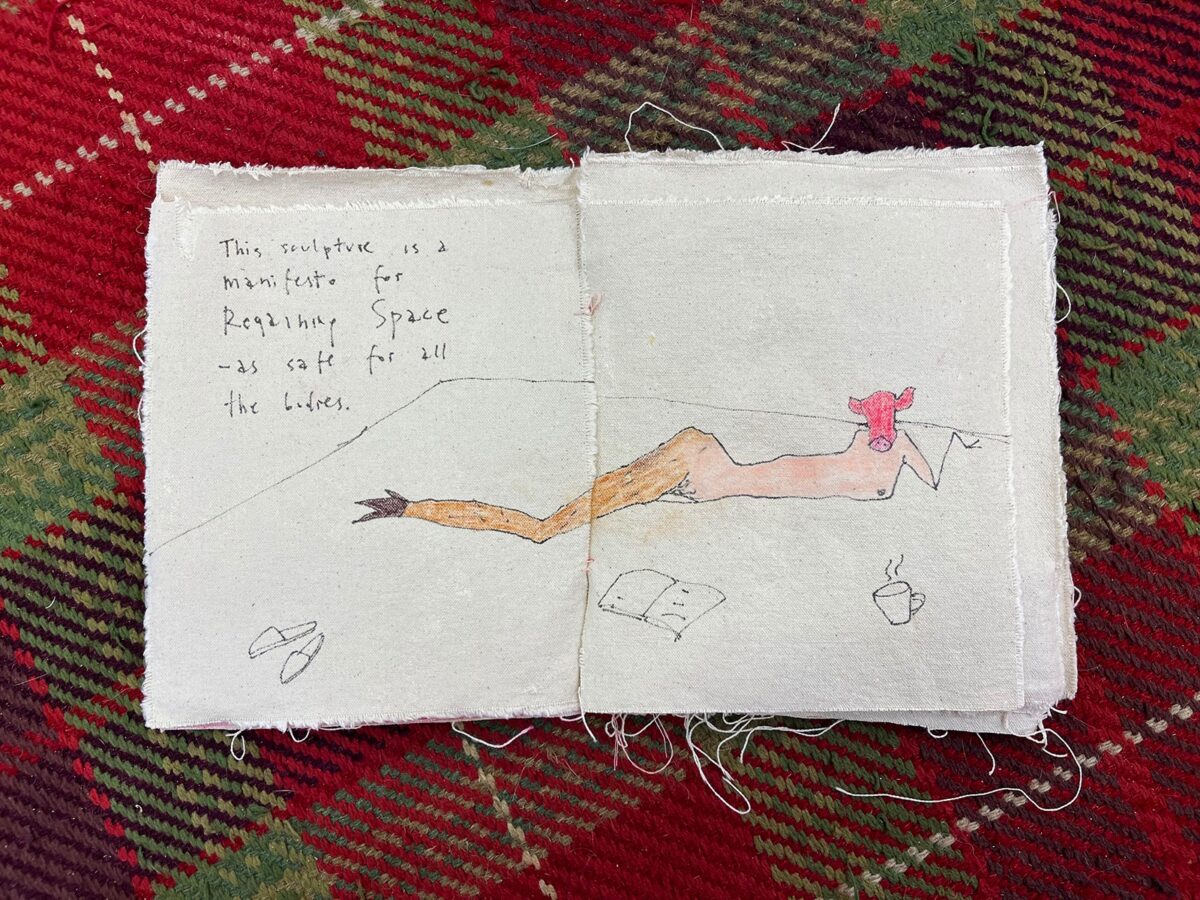

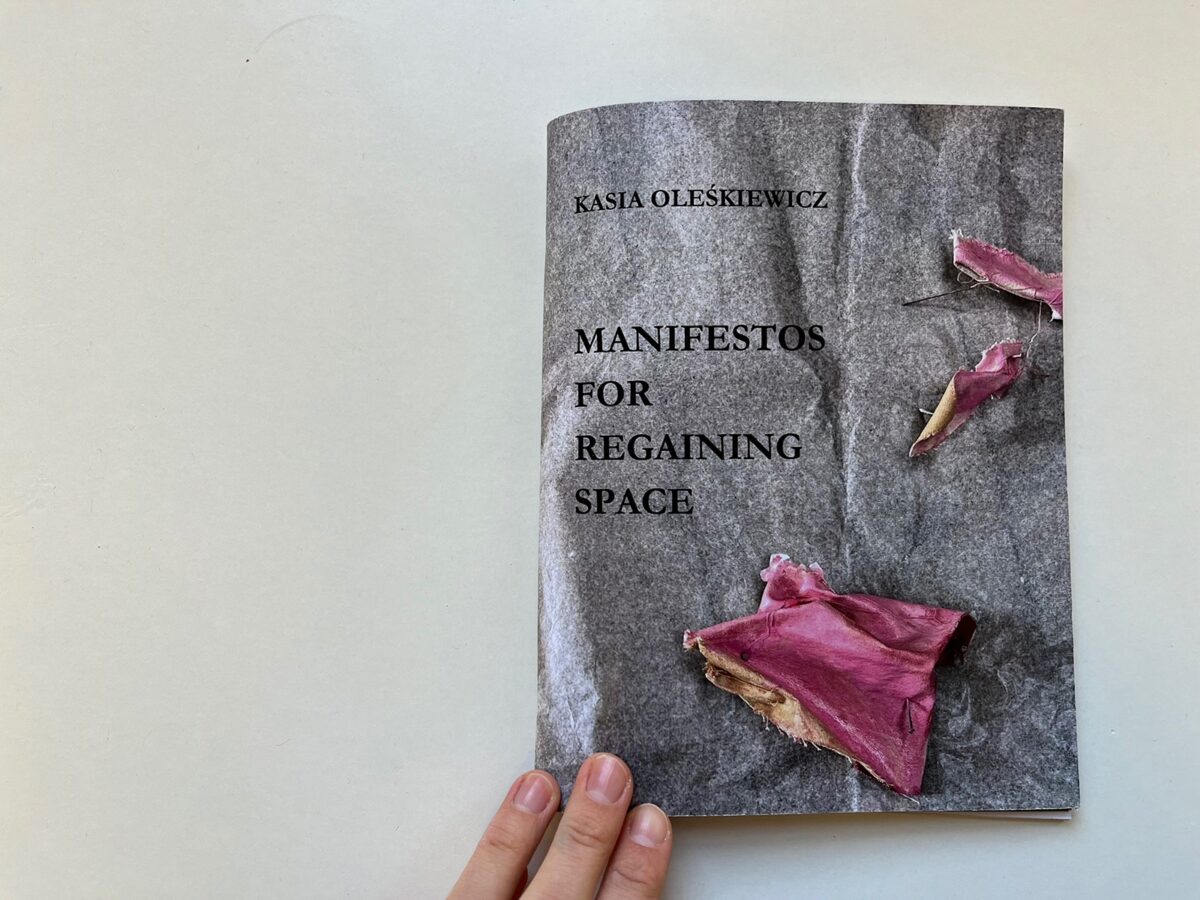

Research project Manifestos for Regaining Space

Location The research was carried during the “Art as Activism” residency; organisers: Hugo Burge Foundation, Summerhall Arts

Hugo Burge Foundation, Marchmont Estate, Scotland (realisation of the artworks)

Summerhall, Edinburgh, Scotland (exhibition)

St Margaret’s House, Edinburgh, Scotland (exhibition)

Can you describe your research project?

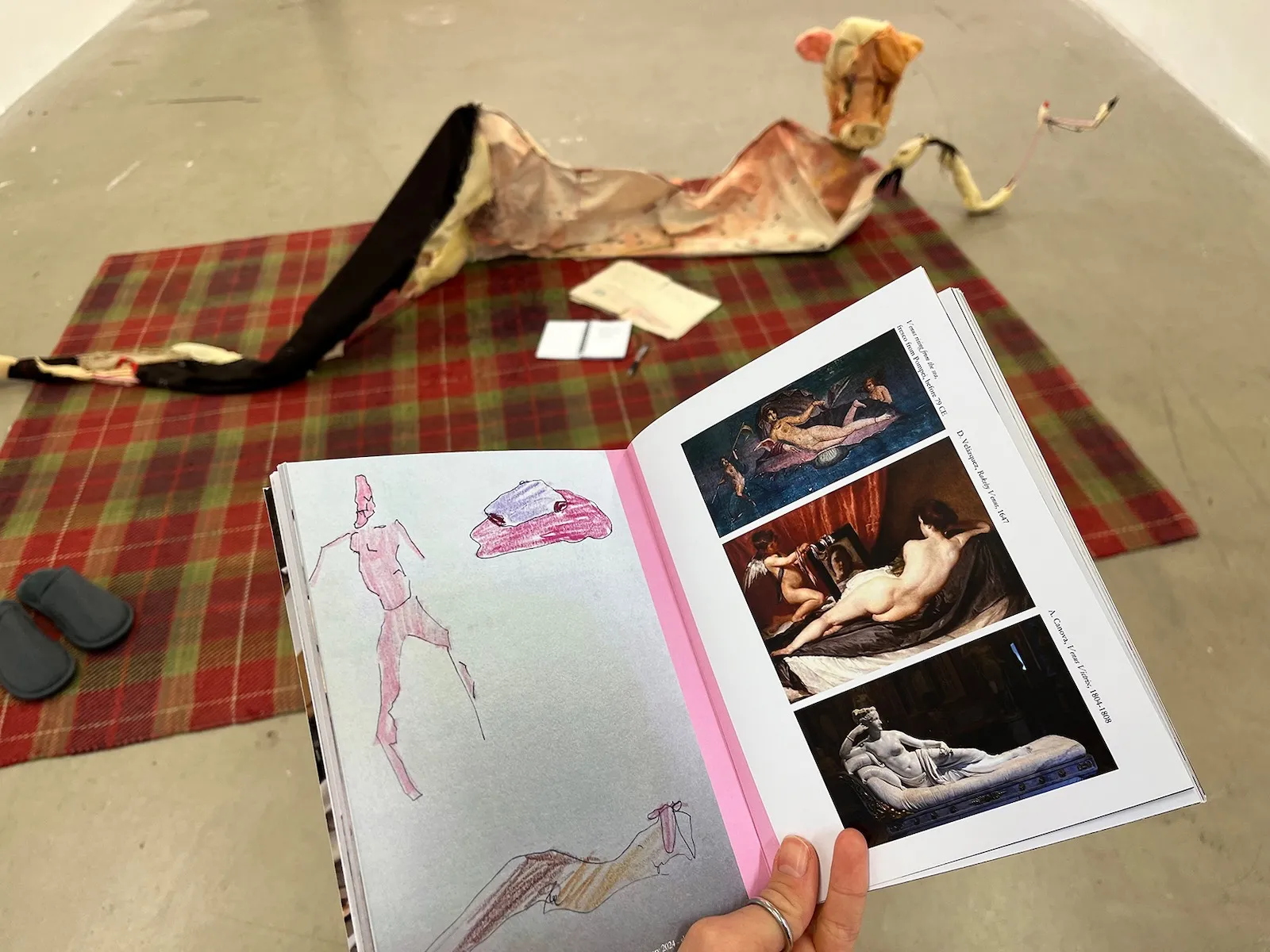

My project Manifestos for Regaining Space explores the topic of violence and unsafety in shared spaces through the lens of intersectional critical animal studies. In particular, I have looked into the parallels between feminism and nonhuman rights. In my work, I reflect on the fear of violence and the power dynamics that shape our encounters, while also expressing the dream of feeling at home anywhere we go. I extend these concerns to all sentient bodies—human and nonhuman alike—through my antispeciesist perspective on the world.

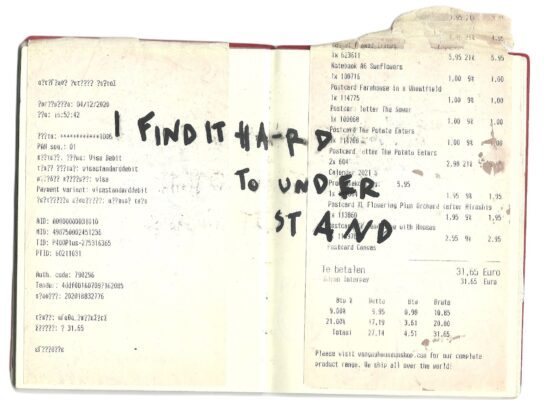

This series includes visual artworks, objects combining sculpture and painting, an artist’s zine, and a catalogue with writings.

Why have you chosen this topic?

The initial inspiration for this project came in February 2024 after hearing about a brutal rape and murder in central Warsaw. For a long time, I struggled to return to normal functioning. My obsessive thoughts intensified, paralysing me with fear. Like many women+ and marginalized genders, I often experience discomfort in shared spaces, given the alarming rates of sexual violence, harassment, and femicide. This crime occurred in the heart of the capital city, early in the morning, with witnesses present.

The feeling of being unsafe anywhere, at any time, lingered with me. I felt a need to reclaim space and cultivate safety.

Although this specific crime triggered my exploration, the project is also the result of a long-standing personal concern. I’ve grown accustomed to being warned about the dangers of walking alone at night or travelling solo, hearing media reports about violence, and reading Rebecca Solnit who wrote about there being nearly a rape each minute in the US. I continually hear stories about this fear, particularly from female and queer individuals.

I see safety and the feeling of being safe as a primary need—vital for functioning, feeling, and living without fear. While safety can never be guaranteed, our patriarchal and sexist culture legitimizes violence, perpetuating this fear.

Drawing from intersectional theories like Carol J. Adams’ The Sexual Politics of Meat, I extend this concern to nonhuman bodies as well. I believe that human and nonhuman rights are intrinsically connected, and that we must abandon the anthropocentric mindset that separates humans from “other animals.” In my work, I envision a future where we talk about “animal rights” as the rights of all beings—human and nonhuman.

I often feel frustrated, saddened, and angry when I see the issue of nonhuman animals being ignored. We talk about being “humane” or call someone a “pig,” revealing how deeply speciesism permeates our culture and language. What hurts most is its absence even in arts, culture or spaces striving for justice. I hardly ever see “speciesism” listed alongside other forms of discrimination (like sexism, racism, homophobia, ableism, and more) in slogans for equality. This is something I want to change.

Nonhuman persons share the experiences of tragedies, violence, disasters or wars, yet our media, commemoration, and compassion usually ignore them, as we have long ago deemed their lives as less important.

Through my work, I seek to address the personal suffering and violence we impose on each other, the position of a body as “given over to another” as described by Judith Butler. I aim to foster change—on even the smallest level—by promoting the dream of protection and creating spaces that are safe and welcoming for all bodies.

What research methods do you use?

My methods are twofold: theoretical and critical research, which involves reading, gathering references, and writing, and practice-based research, which consists of visual artistic work such as drawing, sculpture, and painting. These manual, haptic activities engage my body and facilitate my personal processing of the difficult and painful themes I address—violence and discrimination. In this way, I immerse myself in emotions that are both deeply personal and connected to broader societal experiences, expanding beyond my own body.

As an artist and art historian, I always collect theories, thoughts, and existing artworks, placing myself within a larger context.

One method I use in my visual work is blurring the boundaries between human and nonhuman by creating hybrid bodies. I aim to expose bodily sentience and vulnerability to pain. This also extends to language, where I use “animal” to refer to both humans and nonhumans.

Additionally, I draw from the concept of utopia as method developed by Fredric Jameson. In my practice, I use utopian visions not as unreachable ideals but as tools for critically examining alternative possibilities.

Another method is working from a futuristic perspective, imagining a world after Anthropocene—and what is sometimes called “Sentiocene”. In this reality, the categories of protection, rights, and historical narratives extend beyond humans to all sentient beings. This perspective allows me to think beyond current paradigms and work towards new, inclusive cultural systems.

Inspired by Audre Lorde’s essay The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House, I am not that interested in merely making changes within anthropocentric structures and possibilities. Of course, I support them on activistic levels – because what we can do here and now is crucial. Each small step contributes to a nonviolent reality, reducing suffering, and each saved being is a whole universe. When it comes to art and research, however, I believe their power lies in their potential to develop new tools and bold perspectives. I am interested in total visions of alternative cultural systems. This is why I use art as activism.

For example, one of the sculptures in my series invites interaction: I place it on a blanket with vegan cookies and a notebook where visitors can share their thoughts on safety in shared spaces. This is an attempt to create more inviting spaces and communities, but also to decrease the distance towards galleries and artworks – to find more inclusive and accessible ways of showcasing art.

I also engage my own concept of “animality as method,” which reclaims the term “animal” from its negative connotations. I view animality as a hyper-positive concept, inspiring us to get closer to our true selves. It encourages shamelessness, plurality, and identification with the Other.

In what way did your research affect your artistic practice?

In my art, theory and practice always grow together organically, complementing one another.

Theoretical research is my primary source of inspiration. Intersectional theories have led me to blend human and nonhuman bodies through the creation of hybrid forms which evoke pain and sentience without specifying the owner of the body. I use language specific to critical animal studies, for example using the term “animal” to refer to both humans and nonhumans – to challenge hierarchical thinking and extend post-anthropocentric perspectives that advocate for safety of all bodies.

Furthermore, collecting literature on topics I care about fills me with hope, showing me that the reality I dream of is not unique to me. I find it enriching to know that the foundations of my ideas have already been laid by others, allowing me to contribute to something larger. Much like in activist communities, this sense of solidarity makes the possibility of change feel more tangible.

What are you hoping your research will result in, both personally and publicly?

I hope to contribute to an urgent shift in our collective thinking, one that includes nonhuman persons in discussions about change. Though we face numerous crises and violence, I find hope in the many inclusive spaces and movements emerging today. However, I am frustrated by how often nonhuman animals are dismissed, even within anti-discriminatory art and social initiatives. Our culture and ways of thinking, deeply rooted in anthropocentric mindset, make it easy to overlook or ignore the suffering of nonhuman beings.

I want to see speciesism addressed, much like we have been learning to avoid sexism, homophobia or racism in cultural and social spaces.

Feminist philosophy and movements are recognized more widely than the ones fighting for nonhuman rights, but there is still much to be done and actually implemented. Following Rebecca Solnit, I want to highlight how patriarchal culture and its daily, “innocent” forms of discrimination, diminishment and underrepresentation of women, girls and female-identifying persons contribute to brutal violence.

My ultimate goal is to increase safety for all the sentient bodies, building safer communities through art and culture.

This project holds deep personal meaning for me, as I too struggle with fear and overcaution. I try to cultivate safety in my body, and to reclaim my space. This is something I have been processing and working on while realising the artworks and writings.

To carry and expand this dream of a safer world, I wish to contribute to cultural and political changes, as well as internal sifts towards security and trust.