Based in Paris and Mexico City

Website https://coco.bzh

Research project Archiving Ecosystems in Mutation

Location Field research in various locations in Mexico (with the support of Institut Français d'Amérique Latine), D'Puglia (Italy), and Sumba (Indonesia) at Cap Karoso.

Can you describe your research project?

My research focuses on ecosystems under intense pressure, such as open-pit mining sites, insect migrations, or eroding coastlines. I work with these territories through visual and olfactory landscapes, approaching matter as a process of transformation rather than a stable form.

I develop several interconnected bodies of work. They don’t function in isolation. I don’t work from a single material. What interests me are the passages between materials, scales, and narratives.

The MINERALIS project starts from open-pit extraction sites. I work with metal, stone, or glass profiles, often derived from industrial waste. Crystals can recolonize these surfaces through natural or induced processes. Glass, when fused onto stone, acts as a developer. Obsidian, which is natural black glass, becomes a reflective surface once silvered, close to a landscape painting.

With EXOTIC EXODUS, I integrate tiny insects into tapestries. Like all living beings, they are subject to forced displacement. I’m interested in these movements by shifting the gaze away from the human point of view. When certain environments become uninhabitable, displacement is no longer a choice but a necessity. For the textiles, I work with luxury industry scraps and natural dyes developed with local communities, particularly in Sumba and Mexico. Plant pigments act as landscape archives. Some dyes evolve over time. I have no problem with the piece having its own temporality.

LANDSCAPE MEMORIES is a more recent ensemble that combines tapestries and hollow sculptures diffusing a perfumed vapor, captured under glass. The landscape is conceived with its scent, as inseparable data. Olfaction activates memories that aren’t mine, but those of each visitor.

Why did you choose this subject?

I don’t define myself as an ecological artist. I live in tension with these questions and my behavior isn’t exemplary. The choice arose from discomfort rather than conviction, from a need to confront fragility without the comfort of solutions. Pressure is placed on younger generations, but we could also act politically and think about broader responses—like the planned obsolescence of phones we replace every two years, when they could last ten.

Artists like El Anatsui or Serge Attukwei Clottey have greatly inspired me. They work with waste, but without miserabilism. They make something powerful, desirable from it.

My approach aligns with thinking about planetary transformations, without being militant art. I document geological and biological mutations that exceed human scale, while remaining anchored in very concrete materiality. I feel close to the material turn: treating mineral with the same urgency as living matter, because they’re linked. No minerals without pollinating insects, no flora without soil, no soil without microorganisms.

The olfactory dimension developed over several years. With Laurène Sourdillon at Givaudan, we sought to design a spatial perfume, conceived as a landscape, where several essences coexist in the air. During COVID, I realized that scent can archive what images cannot. The olive trees of Puglia are disappearing, as are certain cliffs subject to erosion. These landscapes have existed for millennia and are changing radically. I wanted to work on this first spatial perfume linked to the Mediterranean coast, specifically Puglia, in a context of flora transformation.

My relationship to deep time is also a way of resisting media urgency. I think art must slow down, observe, let processes unfold. That’s why I work with materials that evolve: crystals, natural dyes, captured scents. My work doesn’t fix anything. It accompanies transformation, it doesn’t fight it.

What research methods do you use?

My method resembles a form of field archaeology. I start by observing, then I search for what means to employ to collect and translate what I’ve seen. Depending on context, I photograph geological strata, 3D scan natural rocks, collect mineral fragments, extract plant pigments, or record olfactory impressions.

An important part of my work remains manual. I weave and embroider by hand. I engrave, I paint, I work matter slowly. I studied traditional crafts in France, and this training still deeply structures my practice.

I work in dialogue with institutions, but also with independent local artisans. In Oaxaca, I collaborated with a glassblower. In Sumba, with traditional weavers. In Guadalajara, as part of a residency with the French Institute. These exchanges aren’t peripheral. They directly orient the form of the works.

Technology intervenes mainly as a collection and translation tool. For olfaction, the approach is very technical. With Byzance World, we’re developing a dry diffusion system, without spray or essential oils, capable of adapting to space through sensors. I also worked with Osmo.ai on olfactory reconstruction through artificial intelligence. The approach differs radically from that conducted with a perfumer and a classic scent library. It’s one tool among others, used for specific cases.

How has your research affected your artistic practice?

Research has profoundly shifted my way of working. The disciplinary boundaries I had learned have dissolved. I no longer distinguish sculpture from textile, nor perfumery from documentation.

By integrating know-how specific to each territory, I’ve transformed collaboration with artisans into the very structure of my work. Craftsmanship is no longer technical assistance, but the engine of creation.

What also interests me in this approach is the idea that matter isn’t inert. It reacts, it evolves, it escapes. Crystals grow according to logics that exceed me. Plant dyes change over time. The insects in my tapestries are real bodies, not symbols. Working with remains of the industrial world—luxury scraps, mineral waste—is a way of showing that beauty can be made without noble materials.

This itinerant practice forces me into constant adaptability. I don’t have a large fixed studio. The field becomes a laboratory. I’ve learned to accept the unexpected, to listen to the scientists and curators I work with. My process doesn’t follow a rigid roadmap. It’s built in encounters and in what I don’t yet master.

What do you want your research to produce, personally and publicly?

I come from Douarnenez, in Brittany, and I have a deep connection with nature and the moving landscapes of the sea. I don’t think art can directly transform public policy, but I believe in its capacity to provoke a sensory confrontation with reality.

Through transformed materials, often derived from remains, I seek to question our way of consuming and our relationship to living things.

Publicly, I hope the research sparks reflection on our brutal disconnection from living systems. We’re all witnesses to change: before, insects flew everywhere when you crossed a field. Today, emptiness sets in. No more insects, no more birds, and certain plants are also disappearing—because they coexist thanks to insects. No more plants, no more scent? And besides, who knows Bangkok’s original smell before the buildings? Nobody. These are all the axes I’m trying to show. This memory functions as a tribute. An alarm, perhaps.

What revolts me is that we point fingers at cosmetic gestures—recycling, replacing your car with a bike—while policies abandon any serious regulation of industrial extraction, intensive agriculture. It’s missing the forest for the trees. Artists have a responsibility: not to give lessons, but to document, to bear witness, to create forms that resist collective amnesia.

I conducted this research first for myself. It finds greater resonance abroad than in France today, which gives me the desire to continue. My objective is to refine my techniques and strengthen this dialogue between scents, landscapes, and volumes. This isn’t finished research, but an ongoing inventory, a way of leaving a trace before certain landscapes disappear completely—minerals or insects alike.

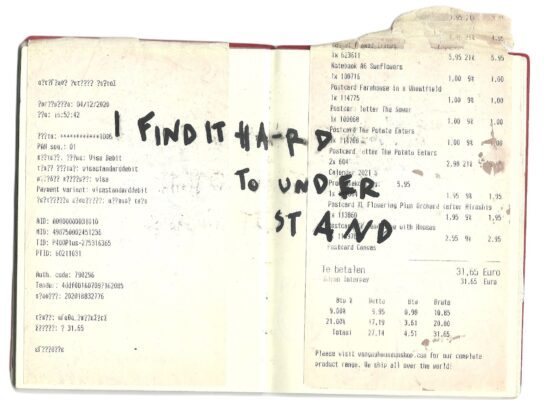

Ultimately, I often wonder: must we necessarily adapt our words to what a society is able to understand? Or should we play with misunderstanding to try to make our interlocutors grasp the blind spots of their own beliefs? I leave the question open.