Based in Berlin, Germany

Website https://bethanhughes.com

Research project Hevea Act 6: An Elastic Continuum

Location The Central State Archive of Film, Photo Documents, and Sound Recording of the Republic of Kazakhstan. Central State Film, Photo, and Sound Archive of Ukraine. Archive at The State Museum Auschwitz-Birkenau in Oświęcim. Institute of Plant Biology and Biotechnology, University of Münster. The Institute of Plant Biology and Biotechnology of the Republic of Kazakhstan and more…

Can you describe your research project?

Hevea Act 6: An Elastic Continuum explores the flexible connections between people, plants, politics, and power through the material and symbolic transformations of Taraxacum koksaghyz — a rubber-producing plant more commonly known as the Kazakh or Russian dandelion. By tracing the journey of the plant — from the Tien Shen mountains in Kazakhstan to collective farms across the Soviet Union, greenhouses at Auschwitz to breeding programs funded by multinational tyre corporations — I aim to offer a counter-narrative to the objectifying, extractive gaze.

Through encounters in breeding facilities, research laboratories, herbaria, mountain valleys, and national archives, I delve into the entangled biographies of the flower and the women whose lives became deeply interwoven with it.

Developed as part of a European Media Art Platform fellowship in 2023, the story manifests as an installation that combines sculpture, video and polyphonic sound. The work has been shown at LABoral Centro de Arte y Creación Industrial, Gijón (SP), gnration, Braga (PT), Kunstpavillion, Innsbruck (AT), and Ars Electronica, Linz (AT). In January 2025, a version will be shown at Silent Green, Berlin (DE). A monograph about the project will be published with K Verlag in early 2025.

Why have you chosen this topic?

This is the sixth instalment of an ongoing artistic-research project called Hevea. Initiated in 2020, the project takes the ancient biotechnology natural rubber as a material and metaphorical starting point to parse the unnatural ecologies created through commerce, industry and technology. Transformed from botanical substance to ritual device, colonial plantation crop to globally ubiquitous commodity, each iteration or act of the project unfolds another thread of this complex human-plant relationship. Each act is produced in collaboration with botanists, scientists, and artists and combines audiovisual installation, sculpture, and text.

What research methods do you use?

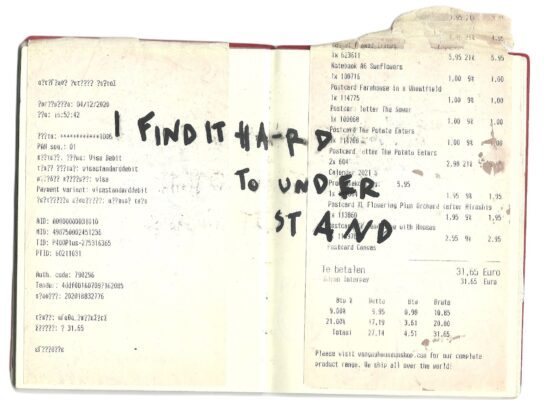

I didn’t know what I would find when I started the project, I simply tried to gather as much information as I could on the Kazakh dandelion and its journey. I travelled to many of the places the plant has been / is bred and farmed, from Germany to Holland, Poland to Ukraine and Kazakhstan. I spoke to people, I took photographs and I asked questions to try to understand their work with the plant and its entangled histories. I looked for traces of it and the women whose lives were connected to it in national and local archives. I read scientific papers about its role as a rubber crop. I found leads on the internet and followed these up, contacting journalists and researchers in other countries. In this way, the project combined journalistic, conversational, embodied, artistic and archival research methods. It isn’t a story that has been told before, so I had to piece it together from many different fragments.

In what way did your research affect your artistic practice?

The idea to create a multi-channel audio installation and a video in seven chapters, each narrated by a different female voice in a different language, was entirely dictated by the research. I discovered many stories and I wanted to give space for each of these narratives to unfold. The installation therefore became a collage of voices filtered through my own aesthetic preferences. The audio, developed with sound artist Diego Florez and played through a series of oversized abstract dandelion sculptures made out of glass, steel and rubber, became a layered composition of field and voice recordings, testimonies, and fictional texts.

What are you hoping your research will result in, both personally and publicly?

Like all my work, the aim is to illuminate an aspect of the everyday that is typically ignored or hidden from view – to point out the industrial, commercial and technological substructures that define contemporary life. The past is so rapidly and comprehensively brushed away by the present, we rarely have time to reflect. There is power in acknowledging genealogy, in highlighting how things – in this case people and plants – are connected. Recognising how and why transformation takes place – over time and through space –– is a way to deal with the future.