How do you describe your own art practice?

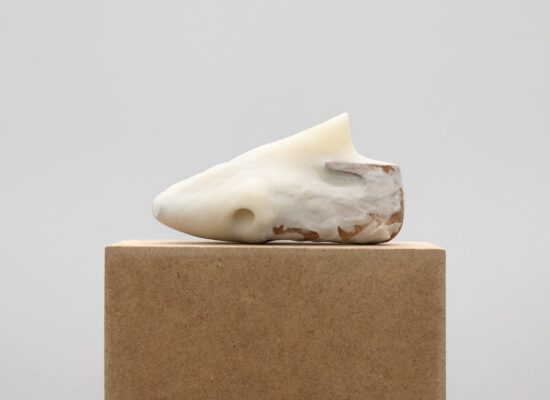

My artistic practice is multifaceted. I’m currently developing a ritual-based creative process that draws on various forms of knowledge to build new imaginaries shaped by both European and South American socio-cultural contexts. I work with fragments of archives, oral narratives – ranging from ancestral legends to personal accounts – encounters, and the transmission of techniques whether related to textiles or not. These epistemic resources carry embedded histories and offer insight into a society’s cultural memory.

My works often involve handcrafted processes and gestures but take on a contemporary dimension in their conceptualization. Through this hybrid form, I strive to articulate a multi-identity heritage and create ritual spaces that oscillate between fiction and materiality. My installations often confront the viewer and occasionally invite them to take an active role. This participatory dimension plays a growing role in my current research.

Which question or theme is central in your work?

My work questions the notion of tradition and cultural identity by examining the intersections between the Andes and the West. I explore the hierarchical boundaries that often separate so-called “craft” from “contemporary art”. Textile structures are at the core of my experimentation: textile language becomes a tool for inquiry, a means of expression. They are sensitive witnesses to the social, cultural, and technological transformations of our time. Through this material language, I seek to explore the complexity of the world in its pluriversality and alterity.

What was your first experience with art?

A traditional aguayo – a rectangular woven cloth used in Andean communities – brought back by my parents from Tarabuco (Yamparaez province, Chuquisaca department in Bolivia), was my first encounter with a woven surface. This cloth sparked in me a distant curiosity. Over the years, that curiosity matured into a focused and detailed gaze. In the Andean worldview, textiles are far more than utilitarian objects. They maintain a deep, visceral connection between the weaver and the land. Beyond their function, they are considered living beings and animated entities that carry memory and act as social agents. I dreamed of this fabric while intimately seeking to understand its creator and its intended recipient through its textile construction. I consider it my first encounter with art, as this textile evokes a constant dialogue within me.

What is your greatest source of inspiration?

I draw inspiration from encounters and from the transmission of diverse forms of knowledge. The places I inhabit become active components of my creative process.

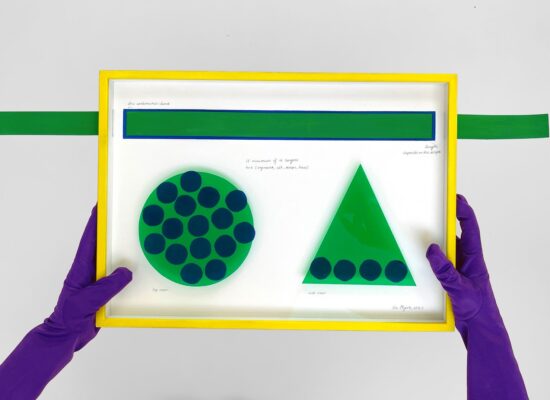

My current research focuses on the aesthetic of the cholas*, a visual language that once served as a colonial tool of domination in the Andes. Through the motif of the pleated skirt, I explore this theme materially and symbolically, deconstructing and reworking its forms. This investigation has been enriched by observing traditional tailoring workshops in Sucre (Bolivia), as well as to the Museo del Traje in Madrid, where I investigated the influence of 17th-century Spanish clothing codes on chola dress aesthetics. These inquiries have allowed me to cross-reference Bolivian archives with European fashion history.

My practice is always anchored in place. During a residency in Barcelona, for instance, I explored net-making, a technique that felt intuitively connected to the nearby sea. To refine my gestures, I received guidance from local fishermen. This technique is now part of my textile vocabulary, which I have also extended through bobbin lace-making patterns rooted in Flemish traditions.

*Cholo / Chola is a Quechua-origin term used during colonization to classify people of mixed Indigenous and Spanish descent in the Andes. Today, the term has taken on a renewed significance, enabling the assertion of a cultural identity often linked to a specific aesthetic, while simultaneously challenging stereotypes inherited from coloniality.

What do you need in order to create your work?

When I create, I need to mentally visualize my gestures and the outcome, it’s a deliberate and conscious act. This process reminds me of Borges’s The Circular Ruins, in which a man seeks to bring his dream to life. In refining my own dream – my protocol – I engage with multiple materials and narratives. It is through this mental architecture that I begin to construct my works.

What work or artist has most recently surprised you?

I recently discovered the work of Brazilian artist Hélio Oiticica (1937–1980). Through his installations, he created living experiences, placing the body and human interaction at the center of his artistic practice. A forerunner of relational aesthetics, Oiticica’s approach resonates deeply with mine. My artistic path has been shaped by various collective experiences, which have greatly influenced my perspective. I aim to develop performative installations that invite audience participation. I’ve collaborated with different performers in exhibition contexts.

I am also sensitive to curatorial approaches. Recently, for the exhibition “Joie collective – Apprendre à flamboyer” at Palais de Tokyo (early 2025), through the work of both French and international artists, the curator Amandine Nana focused on group dynamics and popular cultures. Visitors were invited to take an active role, co-creating a shared space. The exhibition space became public: a site of sociability, transmission, expression and resistance. What struck me most was this powerful will to foster interaction within the exhibition environment.