Lives in Saarbrücken, Germany / Brussels, Belgium

Website https://www.hannahmevis.de

How do you describe your own art practice?

Today, I would describe my practice as multidisciplinary relational sculpture:

Finding the ‘right’ shape is the result of a critical engagement with subject, object and concept. Depending on the context, I can be an artist, performer, mediator, dancer, storyteller, chef, mould maker, teacher, gardener, curator, welder, researcher and many others (yet to come). These processes allow me to meet different people who inspire and/or support my work. The result is fluid and conceptual, often integrating both my own sensory experience and that of the audience. I like to create spaces for active participation and exchange. Ephemerality pairs with physicality as bodies come together to interact. These bodies can be living beings or of material nature.

Holding fruit until the body refuses to perform any longer.

2022-23, performance documentation, video stills, no. 3 of 5 images

Which question or theme is central in your work?

I started with an interest in the human figure and how the body can be captured. This interest evolved into exploring behavioural patterns and ways of creating something that can ‘pass through’ the body – such as sensory/emotional experiences or literally digesting flavours and edible/drinkable sculptures. My ongoing research into the exhaustion of the human body began with the question “What sculptures must feel like holding the same position for a lifetime?” and continued with questioning the role of Western art in the development of stereotypical thinking, binary notions of the body and ideas of normativity. And all of this led me to my recent questioning of whether it is possible to unlearn the social coding and shaping of bodies, and what a self-determined form might look like instead.

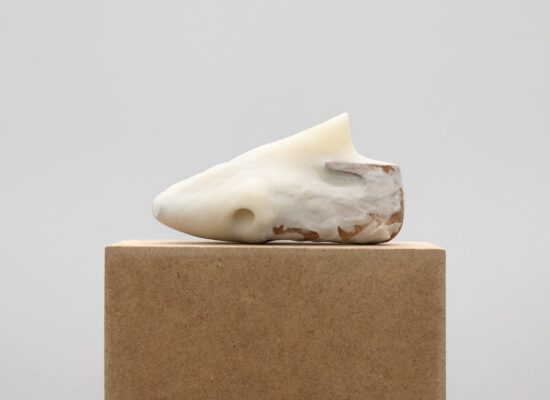

Giving shape to the way my body feels by sculpting in digital, gravity-free space.

2023, 3D printed sculpture created with the help of my avatar and web application called bOdy

What was your first experience with art?

Our mother worked hard to pay for my sisters and me to go to the Steiner School, so I had the privilege of unconsciously accessing an archive of knowledge about materials, fabrics and seasons at school. It was also my mother who sharpened my eye for seemingly unimportant things and nurtured my taste buds. One of my aunts is also a trained artist, but it took me years to recognise the artistic encounters within my family. So my memory of my first experience with art is from the 7th year at the Kunsthumaniora in Antwerp. We had a fantastic history of art teacher. She made sure that she not only guided us through the explanation of a work, but also gave us context about the author, their time, their possibilities and their environment. It felt like an awakening where (contemporary) art suddenly became tangible and made sense to me.

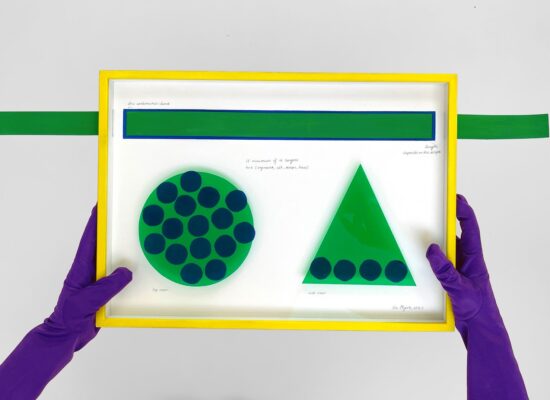

The visualisation of corporeal sensations in a diary-like form.

2023, glass, UV print, steel

What is your greatest source of inspiration?

More and more I find myself struggling with what I call ‘dead’ exhibitions – an exhibition where the works are left behind to focus solely on visuality. The opposite is art that invites you to experience physicality, community, ephemerality. It may be that the artworks actively guide the visitor to move in a certain way, welcome them to lie down for a moment, or invite sensual experiences such as smell, sound, taste, touch. Sharing these experiences gives me a lot of inspiration. But I think my greatest source of inspiration is actually: Participation that allows for process, personal encounters and mutual learning – whether about one’s own body, human/children’s rights, self-determination, sensory perception, observing the overlooked, or allowing a provocative thought and imagination of another world. This creates a kind of energy that truly inspires me. And this inspiration flows back into my studio practice and my motivation to continue doing all the things I do. The more I immerse myself in these experiences and exchanges, the more I believe that my inspiration actually comes from matriarchal skills and knowledge systems.

Dear visitor,

I would like to invite you to experience this work with your senses. Next, you will find introductions on how to approach the glass bubbles. Feel free to follow them or find your personal way. I recommend helping each other! …

Welcome in the bubble and enter at your own risk!

2019, blown glass in three different intensities of the same pigment

Exhibition: “Point of No Return. Attunement of Attention”, NART, Narva Art Residency, Estonia.

Pictures: NART, Hedi Jaansoo

What do you need in order to create your work?

Over time, I have learnt that it is important for my work that I have a secure living situation. It’s probably pretty obvious, but not having to worry about paying the rent is a great freedom. When that freedom is combined with time to move, think, read and process, my work can really flourish. This is also why I find residencies – as a time capsule independent of everyday life – very helpful in creating my work.

In addition, the exchange of thoughts is essential. This exchange takes place primarily with artist friends, but also with audiences, educational institutions or through new encounters during my nomadic states of being.

Corporeal research through dance. Viewers are invited to see the work by moving themselves: “Look at the flag, reach for the ribbon, pull the ribbon to the top left until you can see the whole picture.”

2023-24, flag prints (variable numbers 1-3), steel

Exhibition: “GOSSIP ~ matters hard to grasp” at Cercle Cité, Luxemburg.

Pictures: Cercle Cité Luxembourg, IK & Mike Zenari

What work or artist has most recently surprised you?

Last summer, Chloé, Sina and I visited Luma Arles. While we were in the tower, I was particularly impressed by the charged, humid sky that suddenly erupted and sent lightning bolts across the dry land. Water pushed its way under the entrance doors and the smell of summer rain filled the air. The more we saw of the exhibitions, the more I actually became interested in the art on display. The last building welcomed me with a feeling of shared understanding titled: “Herstory.”

I was drawn to a room that glowed in white light. The closer I got, the more the light drew me into a corridor. As if I were entering the inside of an illuminated snail shell, the corridor led me around a curve into a circular room. At first, it was only underneath my feet, and then I walked through a texture that yielded and compressed under my weight, only to spring back into its former shape as I moved forward. The accumulation eventually reached above my knees. My steps gradually became inhibited, while the movements of my legs travelled through softness like waves. Eventually I found myself back at the centre of that room, bathed in light and the caring embrace of the material. I felt a growing need to immerse myself completely. There were also growing doubts whether it would be a suffocating proposition. While filming the interaction of movement and touch, I accidentally dropped my phone… as it sank to the ground, all sound was swallowed, all light turned to darkness. As I left the room, I was filled with a sense of awe for this radical and timeless work. “Herstory” had led me to experience Judy Chicago’s: Feather Room!

Cloud catching sculpture and participatory cloud drinking event. Venue: from Tuscany into the world. 5ml of cloud juice was sent to 40 addresses in 11 countries on 3 continents. Participants were asked to “free the cloud” again by e.g. digesting it.

2021