How do you describe your own art practice?

With my work, I want to share the stories of my grandparents. By telling their story I am documenting and exploring the past at the same time. I am fascinated about the historical times they lived in. They survived the Second World War, experienced the difficult conditions of the first communist dictatorship in Hungary, took part in the Revolution of 1956, and eventually witnessed the slow transition to a softer regime as the Iron Curtain began to fall. Crazy! That generation was forced to remain silent, with the consequences of being surveilled if you didn’t follow the rules, while I grew up in the Netherlands, free to express my opinions at any time. This contrast interests me.

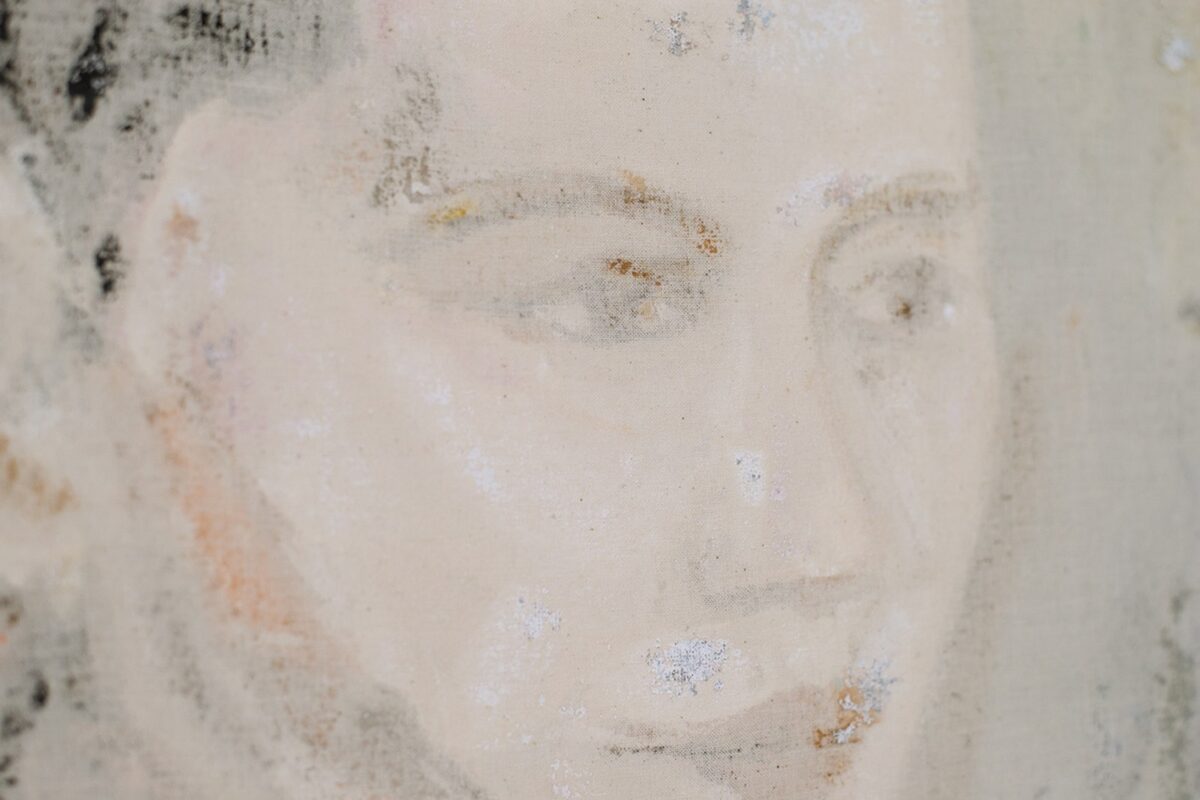

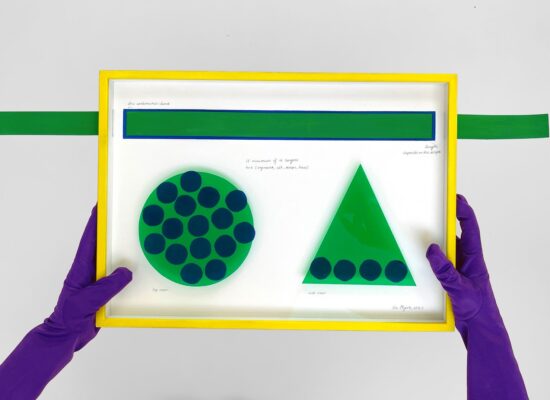

I am interested in how personal and collective memories are formed: About what truly happened, and what has turned into myth over time. In my work, I explore different ways to recreate or tell a memory, searching for the right representation or re-enactment of past events. For instance by instructing people in my video’s, depicting crowds in resistance on a canvas, or with performative readings in which I translated the official state security files on my grandfather. By researching archival systems and working with personal and archival photographs and film stills, I recreate old narratives while inviting the viewer to question what we think we remember.

Which question or theme is central in your work?

Life under the regime, living with the awareness that certain actions or opinions could have consequences, has a lasting impact on future generations. In my paintings, videos, and performances, I explore the effects of the Communist regime, asking how a dictatorial past is processed within a family, by an individual, and in society.

In 2019, I requested the state security files on my grandfather from the Hungarian Historical Archives of State Security, knowing that he had been considered an enemy of the state during the regime led by János Kádár. From a file of 255 pages we learned that my grandfather was closely monitored from 1957 to 1989. In that context, 255 pages doesn’t seem like very much. Where has the rest of the information gone? What does this ‘scarcity’ of documentation tell us about the dictatorial past? Does the current political climate influence the transparency of the archive, and thus our understanding of our own history? Whose rights is the archive policy trying to protect? And what can we learn from the past?

What was your first experience with art?

One of my earliest memories of art is from when I was little and my parents took us to the National Gallery in Budapest. I remember my sister dancing through the museum hall, surrounded by paintings, and me laughing really hard as she twirled around.

What is your greatest source of inspiration?

A great source of inspiration is my grandparent’s old library. It’s full of very old books, in my opinion little treasures. You can find the writings of dictators, historians, freedom fighters, poets, and novelists. But the most fascinating part is that there are also old, censored, illegal first editions. For instance, I discovered the first publication of Kerti Mulatság (Garden Party), a novel by György Konrád. This book was censored and black listed in Hungary till 1988, yet they owned a copy.

Beyond books, talking to people is a great source of inspiration and, for me, a way of doing research. During my residency at AQB in Budapest, I spoke with several individuals who had been part of the former Democratic Opposition and who had known my grandfather. I was eager to learn how they experienced life under the regime and how they found ways to resist. I enjoyed listening to their stories and imagining the moments they described. During another residency at ABA in Berlin, I spoke with the head of the department of the Stasi Archive. There they thought me about how their archive system works and the urgency of an archive, how they help to reveal the past.

What do you need in order to create your work?

Before I start working, I need to write and draw in my diary. I use it to sort out my thoughts, make to-do lists, clear my mind and make sketches. I’ve been keeping a diary since I first learned to write. I have a big box filled with old journals and sketch books.

Besides that, I love the paintings of Joan Mitchell, Marlene Dumas, Helen Verhoeven, Beatriz González, and Susan Rothenberg. The energy in their work always motivates me to start working. Every time I look at their paintings, the brushstrokes surprise me—again and again.

What work or artist has most recently surprised you?

Recently I visited in Porto the Serralves museum where I encountered the work of Nalini Malani – Can you hear me?, 2018-2020. It was amazing! A nine channel video installation with sound, drawings, stop-motion animations, notes and fragmented thoughts. I loved the energy of the piece while it discusses topics such as injustice and other social issues. I stayed in the dark projection room for a really long time.